50 Shades of Red Line

Yeah, I read books.

This is the third post of the ongoing series: "Trade Negotiations, How do they work?" where I provide a glimpse into the inner workings of trade policy negotiations.

In this post I'll be talking about a staple of the trade negotiation space: the red line.

Disclaimer: This post focuses on the tactics of negotiations. It's an inherently subjective area. Please consider these the musings of one person with one set of experiences and not a definitive or exhaustive guide.

The novel 'Fifty Shades of Grey' was published in May 2011. By Christmas that year, your 'cool aunt' had a copy. You have probably not made eye contact since.

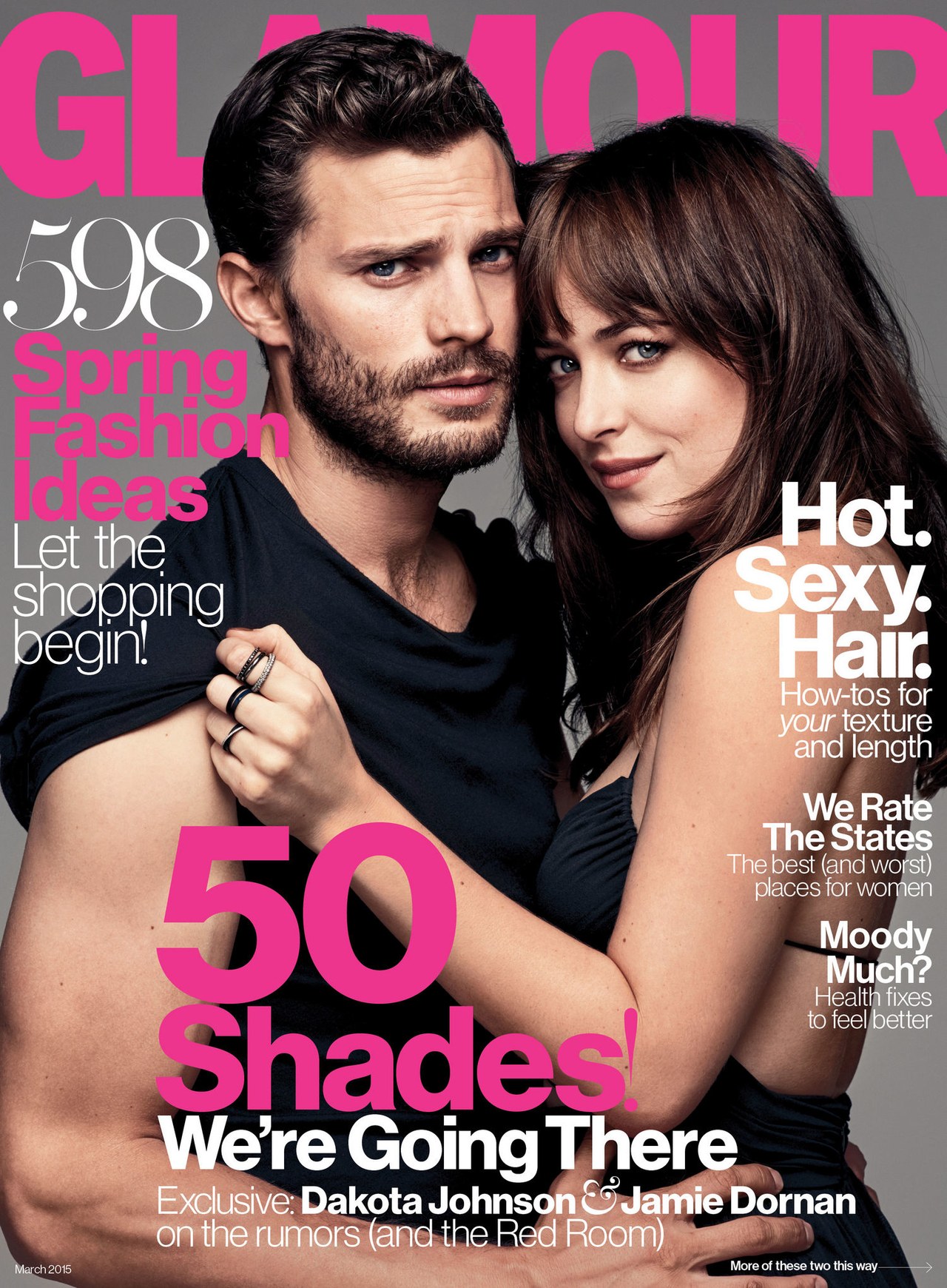

Surprisingly, some of the most vocal critics of 50 Shades' author Stephanie Meyer's literary genius came from the very bondage community her work dragged out of the dungeon and onto mainstream magazine covers.

Yes Glamour you're going there, but maybe you like... shouldn't?

Bondage enthusiasts alleged the books dangerously misrepresent their brand of sexy time, the basic principle of which is consent and clearly set boundaries. In the books they argue, the billionaire with unaccountably defined abs and a lot of spare time during the day ignores or runs right over the boundaries of his partner.

This pushing back of red lines by a partner with greater power and resources, while abhorrent in the whips and chains context is the very bedrock of trade negotiations. I will now opine on this recklessly even though as a trade nerd whose idea of fun is publishing this blog, the most erotic experience I'll ever have is watching someone remove square brackets from around a contentious draft provision.

Mmm yes... now tell your chief negotiator about all this progress we've made you constructive minx.

What is a red line? - The simple answer

Literally defined, a red line is something one side in a negotiation will not accept in the final outcome. Red lines come in both defensive and offensive flavors, with the former being more common.

Examples of defensive red lines:

We won't provide more than a 30% reduction in our tariffs on leather goods;

We won't commit to providing more than 30 years of copyright protection for bondage themed works of fiction.

Examples of offensive red lines:

We won't accept any deal which doesn't provide our exporters tariff free access to your impractically tight t-shirt market;

We won't conclude this deal unless our Dominatrix providers are treated worse than your own when bidding for your government procurement contracts.

Negotiators will try to establish a set of red lines early in the negotiations. Doing so is, depending on how charitable you're feeling either an exercise in transparency, expectations management, or tactical positioning.

It's this third category I want to dig into because the shadow games played around red lines are some of the most interesting elements of a trade negotiation.

Seeing red

If everything negotiators initially claimed to be immovable red line actually was, FTA negotiations would last 15 minutes. Both sides would walk into the room, lay out the full breadth of their red lines, discover they're completely impossible to reconcile, and blow the whole thing off to go to Disneyland.

"Trade Promotion Authority does not extend to 'fun,' I'll need to consult with Washington."

In practice, it is universally understood that not all red lines are born equal. Rather they appear on a color spectrum from the truly immovable to the purely tactical. Over long weeks spent staring at each other across tables in windowless meeting rooms, negotiators work to up-sell the redness of their own lines while probing for inconsistencies or potential flexibility in the red lines of their counterparts.

To put it another way, negotiators are deciding if the issues the other side are claiming to be Kangaroos actually are. If a negotiator can successfully which of the opponents red lines are genuine, they are best placed to trade the minimum amount of concessions for a package the other side will still accept.

Does this provision make my line look red?

Before analyzing the other side's red lines, it's worth characterizing ones own. Knowing which of their own positions are genuine red lines, and why, is important to negotiators even if they don't plan to share that wisdom with the other side.

To illustrate how a trade negotiator might go about this, consider the below questionnaire. Now to be absolutely clear, the below is not a real tool I've ever seen used in a negotiation. Rather, it's an attempt to illustrate the thinking and calculations a negotiating team might make in considering their red-lines.

I swear the 'positioning' heading isn't another 50 Shades joke.

The caution at the bottom of the calculator is crucial. A sufficiently high score in any one category, such as an issue being highly politically sensitive or requiring clearance at an impossibly high level can render an issue into a Kangaroo even if it scores modestly in many of the other categories.

The goal of the exercise is ultimately to help negotiators arrive at answers to three questions on every issue:

Can I move on this?

If yes, what would I need to get in return?

Can I credibly convince the other side I'd need more than that?

Know thine frienemy

Working through a methodical process to understand ones own red lines, their strength and their origin stories (there are no radioactive spiders but plenty of radioactive issues) is good preparation for applying the same principles to the stated red lines of the other side. Understanding why the other side is putting an issue forward as a red line is critical to how hard it should be pushed and what form that pressure should take.

Example: The issue is highly politically sensitive for the other side.

This is a significant concern, but worth closer examination. For whom is the issue a top priority? An issue which strongly polarizes the electorate along traditional party lines may not concern the government as much as one with a more cross-cutting constituency. Is the outcome on this issue likely to change the minds of those concerned about it on the agreement as a whole?

It's also a claim which can be tested with a bit of research. Is there polling on the issue publicly available? How often has the issue been raised in the press? Is there a clearly identifiable and effective public opinion campaign around this issue?

If a negotiator concludes the issue is of genuine political sensitivity, their approach may change accordingly. They know pushing the issue is asking the other side's government to take on considerable political risk. They might push anyway and see what reciprocal concessions are demanded, drop the issue, or consider how the request can be modified to provide the other side with political cover for an agreement.

Thanks to her passion, the mountain killing provision was ultimately removed from the TPP.

Conclusion: Can't we all just get along?

It's reasonable at this point to ask why all the mummery if trade negotiations are all about win-win? Why do countries push so hard on the red lines of others and resist making concessions of their own by inventing red lines to be defensive on?

The answer is complicated and could be a blog in its own right. Here's a heavily truncated version:

First, concessions mean pain. While free trade agreements are win-win in the aggregate they can still involve governments giving up market protections or policy flexibility they'd rather retain. If by 2018 a country (especially a developed one) still has measures significantly preventing foreign competition, there's probably a reason. Lowering that protection and allowing foreign competitors access on a more equal footing is politically painful, or they'd have done it already.

Second, mismatched pain and gain. Imagine a country with a small protected auto sector and a large liberalized agricultural sector. In a free trade agreement negotiation, it would likely push for lower tariffs for its agricultural exports and might be willing to allow more competition in autos in exchange. This is the logical deal to make, and one that's good for the economy in the aggregate, but the car makers facing increased competition aren't helped by improved export conditions for corn farmers.

Third, exclusivity. A free trade agreement provides a competitive advantage against exporters from other countries in one another's markets. The bigger the concession made in a trade agreement, the bigger the competitive advantage. However, the less painful a concession was to make, the more likely a country is to offer it to others in future trade agreements, or even to liberalize for everyone. Hard to win concessions have more staying power, and are thus more attractive.

Combined, these and other reasons mean trade negotiations between even the friendliest countries are tense, grueling affairs rife with deception and mummery, much of it focused on red lines.

I hope you have enjoyed this post in the negotiation tactics part of the "Trade Negotiations, How do they work?" series. As always I remind you this is just one view on how to approach trade negotiations and you should treat it with all the skepticism of a Christian Grey bondage contract.

Other negotiators will have contradicting or complementary takes, and I would encourage you to heed them well.

As always, if you have any comments, suggestions or cleverly worded abuse feel free to leave it in the comments below or tweet it snark at me.