Impossible Trade Promises

August 22, 2025

Articles

00

min read time

Dmitry Grozoubinski

Why Smart People Promise Trump Impossible Things

There are endlessly entertaining videos online of pranksters going to Italian restaurants and breaking every rule of Italian cuisine within the eyeline of horrified waiters.

I confess that my first reaction on seeing trade agreement provisions promising billions of dollars in investment orspecific defence procurements was not too dissimilar from an Italian waiter's watching someone cut spaghetti with a pair of scissors.

“Luigi... get my gun.”

Except I know the people doing things like this aren’t stupid, and they’re not amateurs. Sabine Weyand was in the room for the EU, is better at this than I could ever hope to be and is certainly not in the business of doing things thoughtlessly or without purpose.

So what’s going on?

Join me as I ruminate.

Why is this weird?

Let us start at the beginning – why did I instinctively recoil from the big investment, defence, and energy commitments that litter the Trump administration’s deals with the EU, Japan, and now South Korea?

Trade agreements as we have traditionally understood them are kind of like contracts between governments. They are designed to provide as much clarity as possible about what each government has promised to do, and to be written in such a way as to allow subsequent legal interpretation should a disagreement arise.

To make this work, negotiators adopt certain formulations and conventions so that anyone interpreting the agreement can separate concrete promises from sentiment or rhetoric.

The classic example every law student knows is that in a treaty the word “shall” signals a legally binding commitment to do something, while the word “should” is a significantly less concrete general sentiment.

When negotiating, governments are generally very cautious not to accidentally or through careless drafting make binding commitments of the ‘shall’ variety in areas where they can’t reasonably control delivery – this is to avoid later being found in breach of their obligations through no fault of their own.

As a government, I can make a binding promise that I won’t pass laws or regulations that keep your washing machines out of my market, but I can’t promise anyone will buy them – that’s not up to me.

By this traditional framework, the European Union Commission promising in a deal that the EU will invest billions in the US, buy US energy products, and procure US military equipment seems like a huge faux pas. The Commission has no control over private investment flows, has limited input into where companies source LNG or oil, and has almost nothing to say about the military purchasing of member states.

In other words, it’s made a bunch of promises it can’t control delivery of. That should be a huge red flag.

If not commitment, why commitment shaped?

When confronted with people smarter than you doing something you find baffling, it’s worth taking a deep breath and thinking through their reasoning in case you’ve missed something1.

I came up with a few (not mutually exclusive) explanations.

Explanation One: Time Was Short and the US was Pushy

Like the Brexit negotiations over a transition period and trade agreement, the current talks with the US are fundamentally different from the way we ordinarily conduct trade negotiations.

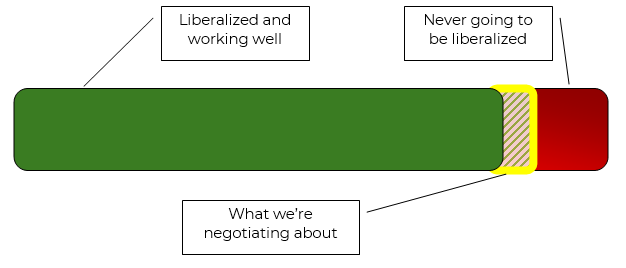

When say, the European Union and Australia sit down to negotiate a traditional free trade agreement the state of play consists of:

1. Mostly liberalized (no tariffs, regulations are fine) trade that’s working well;

2. Some protected or restricted forms of trade that are going to stay that way; and

3. A negotiation over a few areas of trade that aren’t as liberalized as they could be, but aren’t so sensitive that there's no chance of liberalizing them in an agreement.

In other words, you have a situation that’s fundamentally fine and could stand to be a bit better.

When that’s the case, there’s no burning economic urgency2 to get a deal done, to offer more than you’re comfortable with, or to push the envelope.

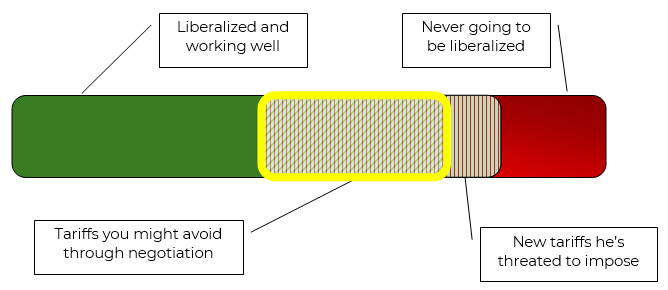

What the Trump administration is doing is fundamentally different. They are setting deadlines and ultimatums by which, if no deal is reached to their satisfaction, they will significantly roll back existing liberalization.

This is a lot more pressing because existing liberalization is a more precious economic commodity. There’s an excellent chance that businesses are currently making use of it and will suffer if it's taken away. By contrast, potential liberalization in a more traditional trade agreement is something business may take advantage of in the future but don't currently rely on or need.

Under this circumstance, with billions ofdollars in trade under threat and a looming deadline drawing closer, the temptation is to push the boundaries on what might otherwise be unacceptable.

If the price the US demands for backing-off on trade paralysing tariffs of 30% or more is a bunch of unfulfillable promises that feature large numbers that sound impressive in a press conference, I can understand the temptation to go “screw it, fine, whatever.”

This is doubly true if you can convince yourself that the commitment is…

Explanation Two: Technically Correct, the Best Kind of Correct

EU direct investment into the United States last year was about $205 billion. If the annual figure remains somewhere in that vicinity this year and each subsequent year for the remainder of Donald Trump’s second term then that brings the total to about $600 billion – which lines up nicely with what was promised in the deal.

The EU could therefore make the case that on paper, if you squint and pretend you're very stupid, it is meeting the obligation it agreed to on investment.

Similarly, a general move to rearm Europe and significantly increased national spending on militaries across the continent will inevitably see more purchases of US military hardware. The US makes some good exploding stuff and NATO interoperability is a priority, so if governments are spending billions more on defence procurement then some of it will inevitably end up going to US firms, sort of living up to the commitment.

Even the energy commitment could be argued to be technically achievable provided one doesn’t specify a denominator – in other words over how many years Europe is expected to spend $750 billion on US energy and energy commodities. Europe buys a lot of energy from the US already, and will likely buy more moving forward as it weans itself off Russia as a supplier. If you stretch the timeline out long enough then even $750 billion is achievable.

Plus, negotiators may be operating on the assumption that…

Explanation Three: Do or Do Not, There is still Try

There may be a hope that the US will ultimately judge adherence to a deal not on the letter of what’s in it, or the quantitative data, but on whether they judge you to be trying.

I have said before that the US can currently be described having something of a vibes-based trade policy – one guided less by commercial and macroeconomic realities and more by the President’s perceptions of select grievances and how various actors are treating the US generally and him personally.

To that end, it would not be at all irrational of the European Union, Japan or Korea to posit that provided they can demonstrate a good faith, full-throated effort to make progress on investment, defence procurement and energy purchases – as well as generally keeping the Trump administration sweet, then the letter of the commitments won’t matter.

The EU Commission for example can’t compel European investors to invest in US firms, but it could facilitate introductions, engage proactively on regulatory barriers, and generally cheerlead for more capital flows. Similarly it could take a range of steps to grease the wheels of commerce around energy and defence procurement, even if actually buying a barrel of oil or a joint strike fighter is not within its mandate.

As long as the Trump administration feels a given partner is trying, and as long as it can point to a few things as public demonstrations that the Trumpian strategy worked to bring about supplication and progress, then it may not sweat the accounting.

Why am I still nervous?

Reflecting on some of the arguments the partners may have used to justify making impossible commitments made me feel better, but unsurprisingly still leaves me nervous.

On an abstract level, governments using binding commitment language to make promises on things they know they can’t control is not a great precedent. Trade has for a long time been the one area of international law where there was a perception that commitments had weight and enforcement had teeth. A move toward impossible promises suggests that at least when confronted with the US juggernaut, we’re moving away from that.

More concretely, explanations two and three above are something of a double-edged sword. Being cute about complying with the letter and not the spirit of a commitment (say, by counting existing and naturally occurring investment flows against your target total) or inversely making an effort in lieu of hitting your numbers, gives the Trump administration room to declare victory and leave you alone – but it also leaves them plenty of room to do the opposite.

The deals being struck contain innumerable elements where a Trump administration inclined to find grievance or seeking an excuse to go back to the tariff well could claim its partners aren’t living up to their side of the bargain.

Constructive ambiguity works until it doesn’t.

Of course, on the flipside, we also must accept that for the foreseeable future constraints, calculations, assurances and guarantees are illusory.

Even if the deal were impeccably drafted from a legal standpoint and included exclusively commitments that partners would have no trouble abiding by without leaving anything to chance, that would still not be any assurance of trade peace.

The Trump administration has proven over and over again that it is fully capable of going back on treaties it has signed, past statements it has made, and past rationales it has deployed.

We live in uncertain times and US trade policy is changeable, capricious and significantly driven by the whims of one man.

There is nothing you can sign with Donald Trump and nothing you can offer him that guarantees that he won’t wake up at some point in the next three and a half years and decide to deploy or threaten tariffs against you. He likes tariffs, he finds them an effective way of getting attention, engagement and traction, and quite frankly he's rather easily bored.

Under such circumstances, it’s hard to blame anyone for swallowing their reservations and just signing anything that helps them get through the week.

Yeesh.

---------------------------

[1] (Through tears:) This also applies to when you see one of your favourite posters on Bluesky say something wildly out of character. Perhaps you’ve missed the sarcasm, the satire, or the reference, Dave.

[2] There may be some political urgency, if for example a leader has vowedto get a deal done quickly – which is how Australia ends up with vastly more accessto the UK than it expected to get.

More from me:

- Book: Why Politicians Lie About Trade

- Public Speaking (CWG Speakers)

- Trade and Geopolitics Consultancy (Aurora Macro Strategies)